Even dedicated organizational structure geeks - and we at Functionly proudly admit to that description - understand that for many entrepreneurs laying out an organigram or (org chart) may not be their first priority.

It is natural that other things take precedence, such as creating and perfecting that great new product, honing marketing strategies and dealing with the 1,001 issues that demand the attention at any moment. Even in established businesses mapping out roles and responsibilities can easily take a back seat.

However, although organizational structure may not always scream for attention, this doesn’t mean it can or should be ignored.

The close attention entrepreneurs like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Canva founders Melanie Perkins and Cliff Obrecht and Apple’s Steve Jobs have paid to organizational structure betray its importance. For many of these companies, it has been one of the cornerstones of their success.

Luckily, when it comes to drawing up an organizational chart, you don't have to reinvent the wheel.

It is possible to look at companies we admire, or those in similar industries, and draw inspiration from their good practice rather than starting from scratch.

Importantly, the org chart must be easily updatable. As businesses grow, ad-hoc arrangements can quickly become dysfunctional. Growing businesses may find the organizational structure that served them well at one stage no longer works.

Bear in mind that organizational charts change according to scale. Even if one adopts the structure of a key competitor or a business one wishes to emulate, the chart may look very different to theirs depending on the respective size of the companies.

Anyone unconvinced of the importance of this part of running a business should bear in mind one of the key moments in modern business history...

Jobs Strikes Back!

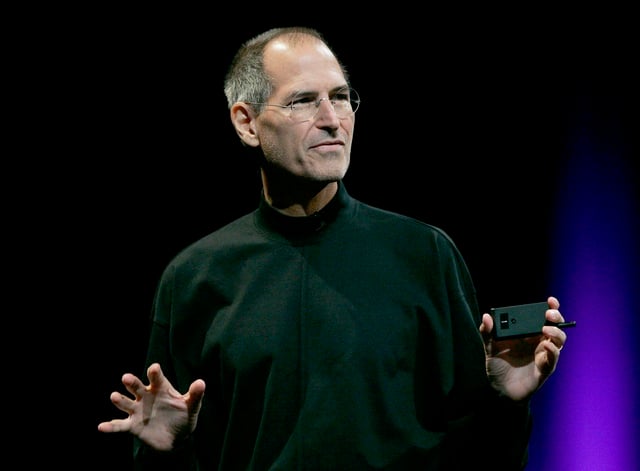

The year was 1997. Steve Jobs – fired 12 years earlier from Apple - had returned to the company.

The previous quarter Apple had published its worst-ever results. Jobs quickly engineered a boardroom coup which saw him re-appointed CEO. One of his first moves was to dismantle the conventional hierarchical multidivisional organizational structure which had grown in his absence.

Steve Jobs made some fundamental structural changes at Apple on his return in 1997. | Photo by James Mitchell / CC BY-SA 2.0.

In reality, this was even more dramatic than it sounds, as it involved dismissing an entire cadre of management in a single day.

Jobs created a new functional structure, where senior vice presidents were put in charge of functions rather than products. Apple has kept the same functional structure despite having grown 40 times larger since.

Given that Apple is now the world’s most valuable company – having topped Saudi Aramco early in 2021 - it is natural that other companies seeking to emulate Apple’s success will want to know how the company is structured.

Crucially, it is important to understand why a functional structure worked for Apple, not just that it works for them.

The “Secret Topping” of Organizational Design

What the Apple story revealed about organizational structure is that it is important to consider the problem at hand before adopting a specific kind of organizational chart to meet it.

As leading organisational design consultant Naomi Stanford put it: “You cannot design something unless you know what it is for.”

Many companies look at organizational structure with vague notions like 'becoming more agile'.

“When you hear 'we must become agile'... it means becoming agile in your context. You cannot just adopt something (because it) sounds like everyone is doing it,” Stanford said.

The genius of certain types of organizational structures lies in the detail of how their structures are implemented rather than their overall design.

On the surface, Amazon - like Apple - has a functional structure that largely revolves around function-based groups. They have an Office of the CEO, Business Development, (AWS), Finance, International Consumer Business, Accounting, Consumer Business and Legal and Secretariat.

But this fails to take into account the famed Amazon “two pizza rule” instituted in the early days by founder Jeff Bezos. He decreed that two pizzas should be enough to feed everyone attending any Amazon team meeting – ensuring teams are kept small and agile.

The secret topping in the two pizza rule is that teams are designed to interact like APIs (Application Programming Interface) – the interface between various often unrelated pieces of software or devices that allows them to communicate.

Jeff Bezos kept all teams within a size that could consume two pizzas. | Photo by Steve Jurvetson/Licensed under CC BY 2.0

What this means is that they receive specific inputs and outputs which can change over time.

Asking the Right Question

When it comes to different kinds of organizational structure, asking a similar question doesn’t always produce a similar answer.

Spotify

Between 2015 and 2019, Spotify’s global subscriber numbers rocketed from 18 million to 124 million – as annual revenue grew to $6.8B.

Spotify’s desire to “scale agile” (as two employees put it in a white paper that famously explained its model) emphasized the importance of culture, which consists of “squads, tribes, chapters, and guilds."

Spotify co-founder Daniel Ek, likes to scale agile. Photo by Fortune Live Media / CC BY-ND 2.0 .

'Squads' are the unit at the base of the Spotify model and are designed to consist of 6-12 people and feel like a small startup business. Each squad has a long-term mission such as building and improving the Android client.

Canva

Sydney-based global visual communications platform Canva has acquired more than 55 million monthly active users and had seen a 130% year-on-year increase in revenue since it was set up in 2012. Founders Melanie Perkins and Cliff Obrecht have catapulted themselves into the list of the 10 richest people in Australia. The company itself is now the 5th most valuable private tech company on the planet.

But Perkins’ and Obrecht’s answer to agility was to eschew traditional company hierarchies and develop “a fluid and freewheeling structure”, experimenting with a concept known as “holacracy”.

Under a holacracy, a lean executive stays off the toes of the employees as much as possible. They provide a strong guiding vision so teams know where they are heading, which then frees up employees to concentrate on performance instead of bureaucratic box-ticking.

Google’s experiments in organizational structure underline the need for adaptability.

You may have read about Google’s famously "pancake-flat” structure – a structure whereby middle managers are rare as unicorns. These days, Google combines elements of flatness within a larger matrix system. This system is also known as the cross-functional – or team-based – organizational structure.

Sergey Brin (left) with Larry Page, who both like it flat. | Photo by Joi Ito | CC BY 2.0

The “ultra-flat” reputation largely dates from a moment just over 20 years ago. Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin decided they wanted to eliminate engineer management almost entirely and quickly abolished the experiment when they found that employees were now forced to contact the CEO with routine administrative questions.

The fact that since 2016 Google, or rather its newly-created parent company, Alphabet, has never been out of the top three most valuable companies in the world underlines the effectiveness of its approach since then.

Corporate Structures to Emulate

As well as being inspired by businesses in a similar area, certain types of structures naturally lend themselves to businesses at different stages of their evolution.

Early Stage: Flat structures are naturally best suited in many cases to early-stage businesses. Having minimal tiers of management allows for maximum agility, rapid iteration, mass collaboration and rapid growth.

In such a business the vision (the "why") is simple, clear and easy to communicate, whereas the strategy (the "how") is fluid. The business engages a high-learning mode and flat structure to allow for rapid shifts in direction in response to every decision or market change.

Mid-stage: here, businesses may well benefit from introducing a functional type structure – introducing department disciplines, and management layers to manage the hiring associated with rapid expansion.

Functional structures often particularly suit companies based around a relatively small range of products. One of the early corporate champions of functional structure were 19th century railroads – rapidly expanding organizations that were largely focused around a single product.

Large: Conventional wisdom states that once companies reach a certain level of maturity they grow too large and complex for a functional structure.

Instead, they should switch to a multidivisional structure to enhance accountability and prevent countless decisions flowing upwards to senior decision-makers.

The theory goes that a multidivisional structure gives business unit leaders full control over key functions and allows easy assessment of performance throughout the hierarchy.

It has become, in many ways the classic corporate progression – a road followed by many major corporations such as DuPont and General Motors.

But companies such as Apple, Google, Amazon, Spotify and Canva are showing that the old rules no longer necessarily apply when it comes to organizational structure.

In the 21st century, it appears, firms can have their structural cake, or even their Apple or their pizza – and eat it.

: Get Functionly!

: Get Functionly!

Are you inspired by these tales of corporate success borne of choosing - and adapting to - the right organizational structure?

You can experiment with your own company structure - for free - using Functionly's drag and drop platform. It's easy to use, online, updatable in real-time and can connect to your HR system (saving you time in uploading all your employees).

Get started today on selecting the best organizational structure and design for your business, with Functionly.

~~